It took me a long time to truly understand why the outbox pattern exists. In this blog post, I want to discuss the problems the outbox pattern solves, how it works, and why it is not a magical solution. I suggest you to read about the outbox pattern if you have no prior knowledge.

the scenario

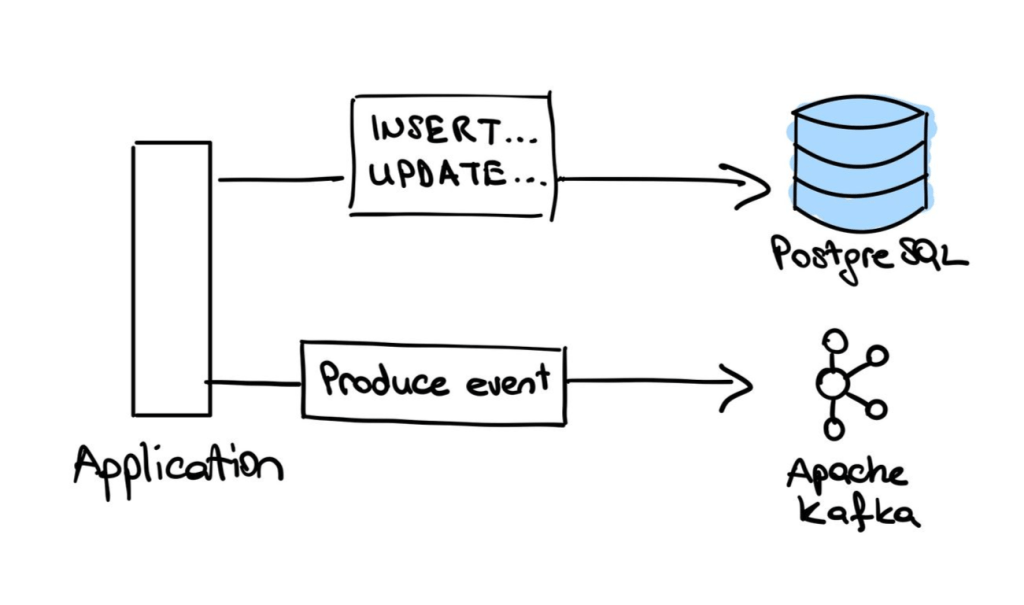

In this scenario, we are working within a microservice architecture where the business logic is distributed across multiple services. We want to

- persist some data on our precious database

- produce a message to a message broker (Apache Kafka, for instance).

The Kafka event is used to communicate with other services. Assume this event also changes some state in another database.

The requirement is, if the database has the change, the event is produced and if the event is produced, the database has the change. Remember, this is our business requirement.

the problem

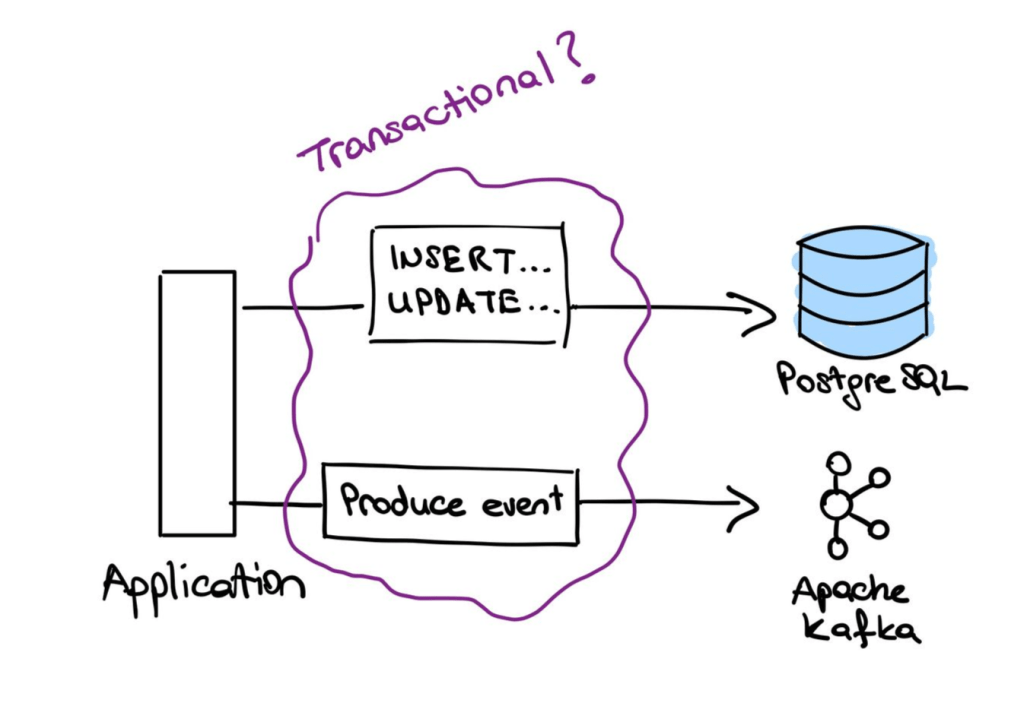

There are a couple of things that can go wrong.

What if an error occurs while we are producing the event? We have two options: retry producing the event until it is successful, or rollback the database change. What if another process reads the data before we roll it back? What if there is an update and we unintentionally overwrite the change while rolling back (i.e. lost updates)? What if there is a network error while we are rolling back the database change?

What if we fail to persist the data to the database? We might violate a constraint in the database or a network failure might happen. How are we going to rollback the produced event? You might argue that we can produce the event if the database query is successful. However, in a complex business logic, this might not always be feasible. Additionally, the domain logic in our application should involve as few technical details as possible, since requirements not explicitly coded tend to be easily forgotten.

one possible solution

One possible solution would be to start a database transaction using BEGIN; keyword, do the database updates, produce the event and commit the transaction with COMMIT; . This way, if there is an error while producing the Kafka event, the database can safely rollback its changes. However this approach also has flaws.

The database is the heart of a business application. It should be responsible only for persisting and querying data. Making the database wait for unnecessary operations such as I/O waits would harm the performance of read/write operations, even leaving it unresponsive under heavy loads.

Managing transactions that involve components communicating over a network is not trivial, and surely RDBMS transactions are not the way to do it.

Distributed transaction management is itself a problem which different software companies such as Oracle has solutions to. You can read more about Jakarta Transactions, for example.

back to the drawing board

There is a common pattern in the problems above: communicating over a network. Lots of things can go wrong when you communicate by network messages. The famous Two Generals Problem is a nice and simple example of this.

Additionally, our requirement that ‘if the database has the change, the event is produced, and if the event is produced, the database has the change’ still stands.

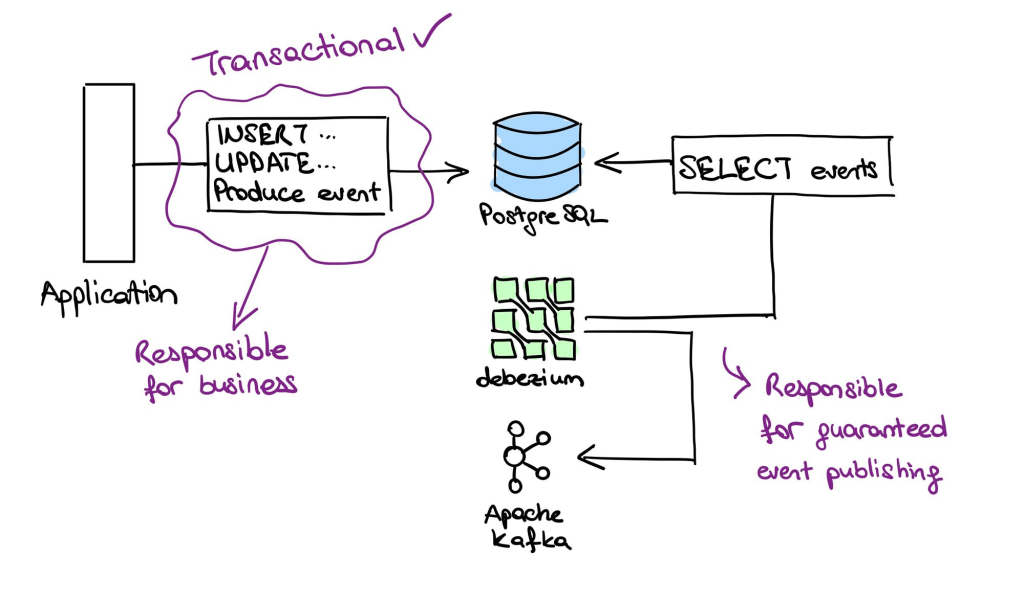

Let’s assume we do not need to produce the event to Kafka explicitly. Instead, we write the events to the database and some fairy will use its magic to transport them to Kafka. This way, we abstracted away the cumbersome network part. Don’t get confused— the problem with communication over the network still exists; we’ve just chosen to abstract it away for now.

This approach enables us to safely use RDBMS transactions. RDBMS transactions are ACID compliant. They are atomic, they leave the database in a consistent state, the ongoing transactions do not interfere with each other and the writes are durable in the disk in the event of a failure. Also, the database handles the rollbacks if any update fails. Once the transaction commits, there is no need to roll back the changes.

the magical fairy

After the transaction commits, the events in the database are safe to be produced Kafka. No database operation can cause the event to get rolled back because they are committed together.

Debezium is a tool that actively listens to database changes and routes the delta to another source, such as Apache Kafka. It has retry mechanisms and it guarantees that events are produced to Kafka at least once. Since this post is not about Debezium and how it works, I will leave you to read about it, later.

what did we do?

Managing transactional changes over multiple datasources which communicate over network is a hard problem. We introduced an abstraction and it allowed us to divide the problem into two subproblems: transactionally persisting data and events together, and producing the events to Kafka. The first problem is relatively straightforward and does not require us to couple technical details with our business logic. The second problem, on the other hand, does not involve business logic and can be solved separately by an open-source project.

The bottom line is that the outbox pattern itself does not solve the main problem. It is a solution to a subproblem which is introduced by an abstraction. The remaining problem about network is a much bigger problem but it is solved by tools like Debezium.